Want to get these in your inbox to never miss an edition? Subscribe to Hospitalogy today

Introduction

Welcome to Part 2 of the new-age health system merger. In this essay, Daran and I will cover why we’re keeping an eye on the future of population health management strategies as health system mergers evolve to prioritize risk and additional sources of revenue diversification.

We’ll also compare and contrast the Advocate Aurora-Atrium and Intermountain-SCL mergers, including our thoughts on whether each merger is likely to raise or lower prices based on historical precedent and the nature of each system’s operating model.

If you missed Part 1, that essay provided historical context for the specific Atrium/Advocate merger, including how mergers have evolved over time and headwinds facing hospitals. Read it here!

I’m excited to be joined again by Daran Gaus, who writes The Scroll. He knows everything value-based care (like, REALLY knows the space), so drop him a subscription!

Key Takeaways

To get mergers past FTC review and to the finish line, health systems in the year of our UnitedHealthcare overlord 2022 are finding more creative solutions and prioritizing different mega-merger strategies.

The two largest announced mergers between Intermountain/SCL and now Advocate-Aurora/Atrium have included pointed language around pursuing risk-based population health strategies, a focus on charity care, medical research, enhanced data analytics, and investment in digital health infrastructure. That strikes me as a major shift in the type of mega-merger we’ll be seeing from now on.

The days and opportunities associated with consolidating JUST to boost market share and command higher payor rates are evaporating in the hospital market. From here on out, health system mega-mergers will look to open different doors that also benefit from economies of scale – like the ability to get closer to the premium dollar to compete with the traditional insurer.

There’s a difference between what two merging organizations say they’re going to accomplish post-merger, and what actually happens. While the jury is still out as to whether or not the Advocate-Atrium merger will prioritize value-based care, I’m fairly confident that Intermountain and SCL will set out what they have proposed in implementing population health management strategies.

Finally, As healthcare organizations continue to engage in vertical mergers, antitrust review of mergers will need to adapt.

TL;DR – Our primary thesis is that health system M&A strategy is shifting from horizontal (market power play) to vertical integration, thinking about upstream and downstream revenue, taking on risk, and becoming more of a fully integrated institution.

Want to get these in your inbox to never miss an edition? Subscribe to Hospitalogy today

New-Age Health System Mergers

While certain hospital mergers have been shut down or challenged, other health systems managed to successfully close large transactions despite similar scale. Why? Because they’re pursuing new population health strategies at scale while at the same time promising job creation, enhanced charity care, and other concessions to appease regulators.

These considerations have created the new-age health system merger in 2022 like we saw between Intermountain and SCL and now, Atrium Health and Advocate-Aurora. While the traditional health system merger historically merged for a play on insurer rates/negotiation, overhead synergies, and purchasing agreements, these last two mergers are much more focused on the risk-based game.

Increased scale also gives the system justification for making riskier alternative investments into health tech players and grow their venture capital book of business.

As Matthew Holt likes to put it, health systems are increasingly becoming hedge funds with a side of healthcare services based on how big some of these endowments are growing!

Join the thousands of healthcare professionals who read Hospitalogy

Subscribe to get expert analysis on healthcare M&A, strategy, finance, and markets.

No spam. Unsubscribe any time.

Blake’s Thoughts & Analysis

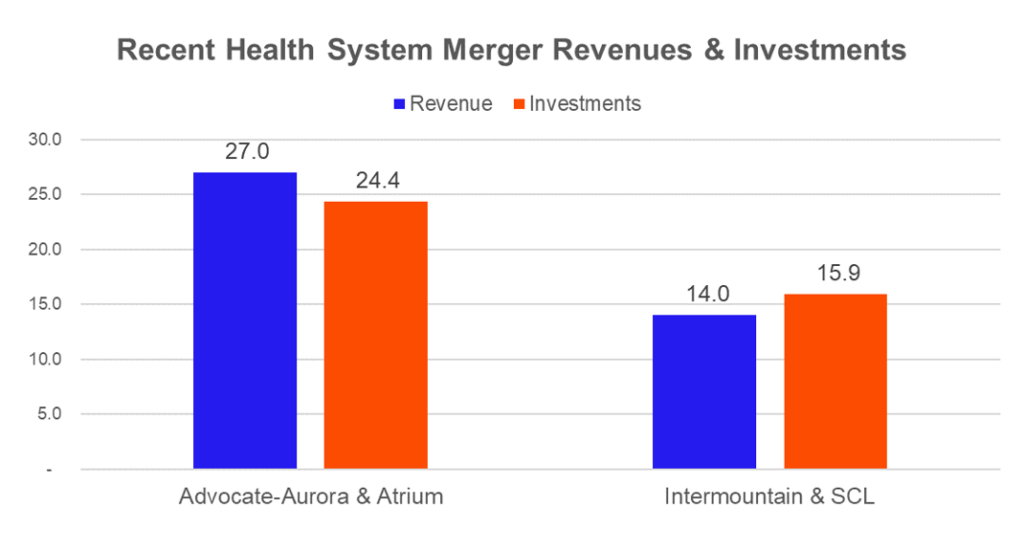

I’ll let Daran get into the juicy stuff on the population health and value-based care side of things, but I do think a silent perk of the new-age merger is the amount of opportunity and incubation available on the venture side. SCL and Intermountain are sitting at $14 billion in revenue, while Atrium and Advocate’s combined figure amounts to around $27 billion.

Meanwhile, Intermountain’s investment fund sits at around $12.8 billion. SCL’s at $3.1 billion. On the Atrium side, investments are around $11.2 billion, and Advocate’s is $13.2 billion.

The combined scale, despite the lack of geographical overlap, provides these systems with other avenues for growth, namely in the alternative investment category and venture. For instance, Intermountain just partnered with General Catalyst, which has an impressive track record and portfolio of private digital health assets.

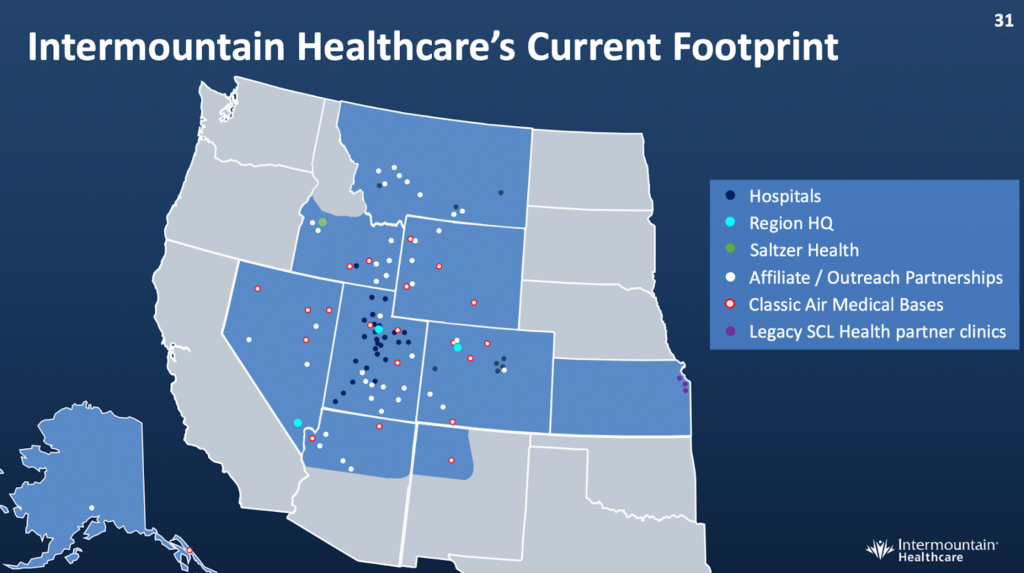

Source: Intermountain Investor Presentation

Given the combined revenue base and diversified revenue streams across geographies, it becomes easier to justify allocating a larger proportion of endowment investment dollars to riskier, but beneficial digital health and other firms. Now more than ever, hospitals are facing multiple headwinds and need to find ways to improve efficiency within their existing infrastructure, and I’m willing to bet the companies supporting those initiatives will win big here.

Think about how quickly a health tech or other startup could grow if scaled within one of these monster organizations. That has to be on the table here, right?!

Daran’s Thoughts & Analysis

Remember in Part 1 when I said we were going to revisit if mergers are good or bad for patients? Well here we are. Fortunately, the timing of the Intermountain-SCL merger and the Advocate Aurora-Atrium merger gives us the ability to take a hard look at (and hard listen to) the nature of each transaction to determine if it is more or less likely to meet the IHI Triple Aim of improved patient experience (quality and satisfaction), improved population health, and reduced cost of healthcare.

A Tale of Two Mergers

Here’s my (Daran’s) working hypothesis: providers consolidation will increase prices unless there is a deliberate and explicit effort to do the opposite, and for that to be true, one or both of the merging parties must have a well-established track record of value-based care.

Methodology: In an attempt to evaluate each health system’s progress along the value-based payment continuum (ranging from pure FFS with no link to quality all the way to population-based payments), we evaluated each using the value-based care tipping point framework developed by Deloitte (which basically says that when 40% of a health system’s revenue is at risk, then that health system is value-based). We are also channeling a little bit of Malcomb Gladwell’s take on casuistry (as these mergers appear pretty spectral).

Sticking to Deloitte’s play-by-play proved exceptionally difficult as audited financials based on GAAP reporting [materiality guidelines](https://www.tgccpa.com/2018/03/how-materiality-is-established-in-an-audit-or-a-review/#:~:text=To establish a level of,specific financial statement line item.) are sufficiently ambiguous to obscure the true data points that would readily be available within a health system. Thus, we made some assumptions based on the publicly reported data and reconciled them against what the health system claims to be doing in order to establish a reasonable degree of certainty for the health system’s dependence on FFS.

What they said.

There was a pretty notable difference in tone between the Intermountain/SCL merger as opposed to the Advocate/Atrium merger.

Intermountain / SCL: Intermountain was extraordinarily vocal about its merger intentions. Chief Financial Officer Bert Zimmereli explained the company’s outlook at this year’s J.P. Morgan Healthcare Conference, “We’re very committed to demonstrating that this merger will not drive up healthcare costs. In fact, our goal is to help show that we can, through growth, make healthcare more affordable.”

Full stop. I think we’ve heard enough to understand how Intermountain plans to bend the cost curve.

Advocate Aurora / Atrium: Eugene Woods, president and CEO of Atrium Health (and future CEO of the conglomerate) said, “this strategic combination will enable us to deepen our commitments to health equity, create more jobs and opportunities for our teammates and communities, launch new game-changing innovations and so much more.

Together, we will manifest a new future that significantly elevates the care we provide to every hand we hold and every life we touch.”

The overall release messaging focused on clinical excellence that will catalyze future success in six key areas:

- clinical pre-eminence and safety,

- health equity,

- affordability,

- next-generation workforce,

- learning and discovery, and

- environmental sustainability.

There was plenty of talk about population health, innovation, and leading the industry’s transformation. You may think that I’m cherry picking, but the contrast between explicit intentions and healthcare buzzwords is palpable. Or, maybe that’s just the difference between a couple of PR agencies. We’ll let you guys be the judge of that!

Looking at surface-level press releases won’t really give us a full picture of organizational intent, though. An organization’s track record is a better predictor of the likelihood that a merger will improve population health and drive down healthcare spending rather than what they say in a press release. Fair enough. Let’s dive into what these organizations have achieved in population health management.

What they’ve done.

In order to examine the likely directionality of costs post-merger, it is useful to examine exactly how steeped in fee-for-service (FFS) each party within the transaction is. Said another way, what does each party’s value-based care footprint look like and is it material enough to matter? In order to assess this we will take a peek at each health system’s profile (Figure 1), financial reporting (Figures 2) and preponderance of evidence to support success in value-based care (Figure 3).

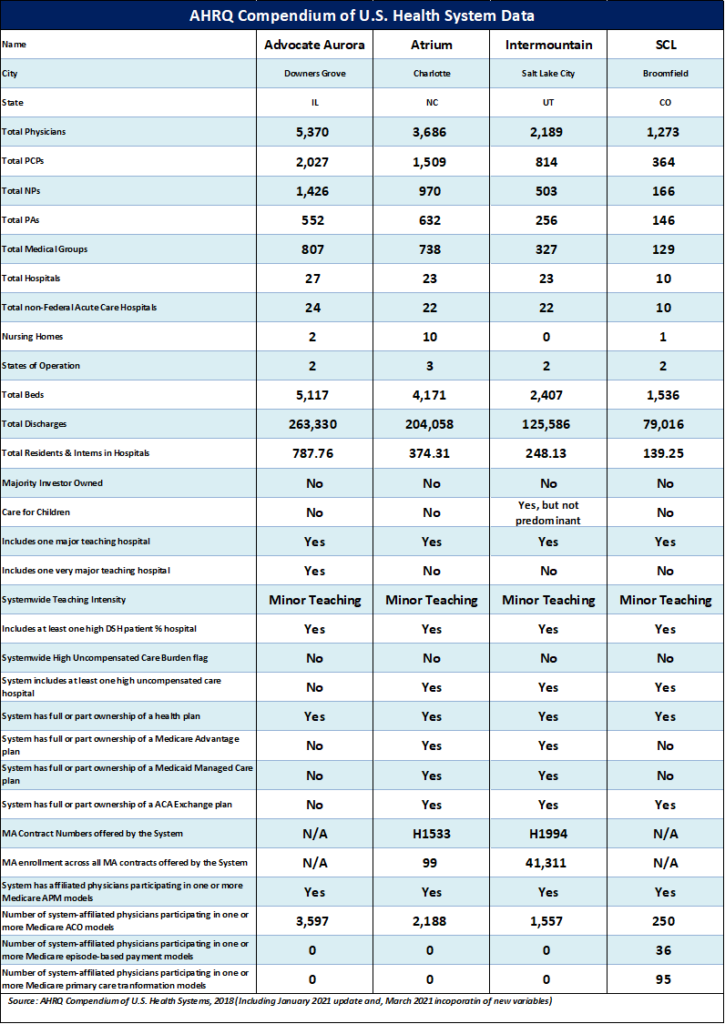

Figure 1: health system profiles. Source: AHRQ

Advocate Aurora

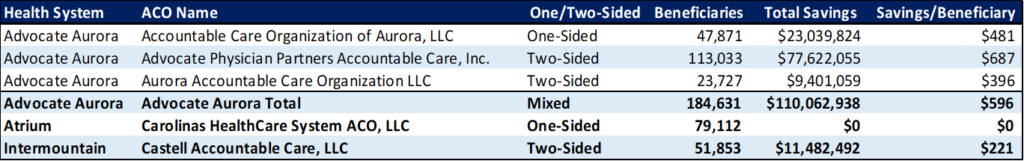

Advocate has three affiliated ACOs (Advocate Physician Partners Accountable Care, Inc., Accountable Care Organization of Aurora, Inc., and Aurora Accountable Care Organization, LLC) participating in the Medicare Shared Savings Program. These programs are Advocate’s strongest evidence for advancing the value-based care cause.

In 2020, the affiliated ACOs saved $110M (a feat that prompted the organization to publish that it leads the nation in savings) for the Medicare program which resulted in a shared savings payout of $56M to Advocate Aurora.

Collectively, that figure beats Baylor Scott & White Quality Alliance’s $96M, the largest nominal single ACO savings performer. This is bolstered by the fact that nearly ⅔ of Aurora Advocate-affiliated physicians participate in an ACO model (Figure 1).

The total savings may be misleading as the number of at-risk lives directly correlates with the potential savings achievable. Thus, to provide a more apples-to-apples comparison of performance between ACOs, we can look at savings per beneficiary. When we parse the 513 ACOs that participated in the 2020 MSSP performance year, Advocate Aurora’s ACOs rank #126, #211, and #256. Thus their performance is likely driven more by size than by truly moving the needle on driving down healthcare spending.

That said, it is commendable that all three ACOs were near the mean or better on a savings per beneficiary basis (168 ACOs failed to generate any savings). Accounting for whether or not the $110M was truly stellar is a matter of materiality.

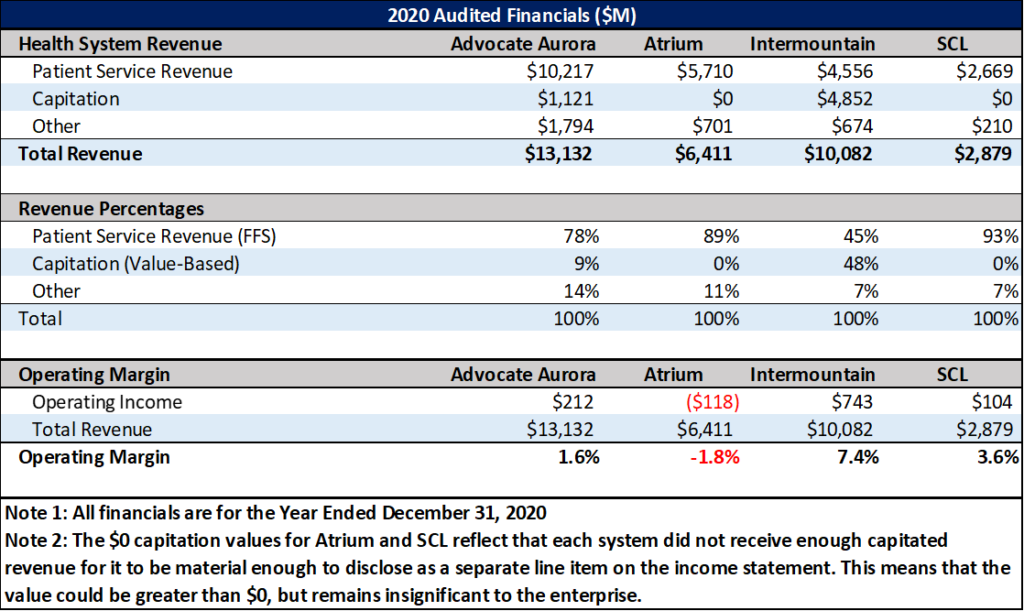

Figure 2 below shows that Advocate Aurora’s total revenue for 2020 was $13.B, of which $3.1B came from traditional Medicare Payments.

Figure 2: Health System Financials

Translation: Had Advocate Aurora had achieved zero savings, it would’ve impacted just 3.4% of its total Medicare revenue and a mere 1.1% of its patient service revenue. In other words, the ACOs may have done better than other ACOs in total nominal dollars, but the savings isn’t material to the $10.2B in FFS patient service revenue as of 2020.

Advocate Aurora recognized $1.21B in capitation revenue, which was material enough to report (Figure 2), but the combination of capitation and shared savings – a combined 10.8% of total revenue – tells me that Advocate Aurora is still light years away from the 40% of revenue inflection point at which the system’s operating model shifts away from FFS to favor VBC.

On the payer side, Advocate Aurora partnered to launch two Medicare Advantage HMO plans in 2021, one with Quartz (the Aurora Health Quartz Medicare Advantage plan) and the other with Blue Cross Blue Shield of Illinois (the Blue Medicare Advocate Health plan).

The Quartz plan has 2,210 members and the Blue plan has 818 members as of May of this year, and the nearly 3,000 members will not be a large enough population to turn the FFS tide at Advocate Aurora.

To its credit, the health system established a partnership with value-based primary care provider Oak Street Health in 2019 to care for Chicago-based seniors. While this is certainly a value play on paper, it appears more like Advocate Aurora is happy to let Oak Street “do its thing” rather than learn from its model. The upside for Advocate Aurora is likely fewer acute Medicare admissions, an area the hospitals are fond of highlighting as an area of unprofitability. Additionally, Advocate Aurora acquired MobileHelp, a home-focused provider of remote patient monitoring (RPM) capabilities and personal emergency response systems, and the home care franchise Senior Helpers over the past two years. So they are certainly occupying multiple points along the care continuum.

As a final nail in the coffin, Advocate Aurora’s contracting policies are under fire as they are currently being sued by using all-or-nothing contracts to inflate prices in Wisconsin. While the presumption of innocence exists until proven guilty, historical behavior points to likely malfeasance on Advocate Aurora’s part.

Daran’s Verdict: Fee-for-Service dominates Advocate-Aurora’s current operating model.

Atrium

Of the two, Advocate Aurora is the clear value-based leader in the context of its merger with Atrium. Atrium does participate in the MSSP program, but has yet to generate any savings for the Medicare program to date. Notably, 57% of Atrium-affiliated physicians are participating in the program (Figure 1).

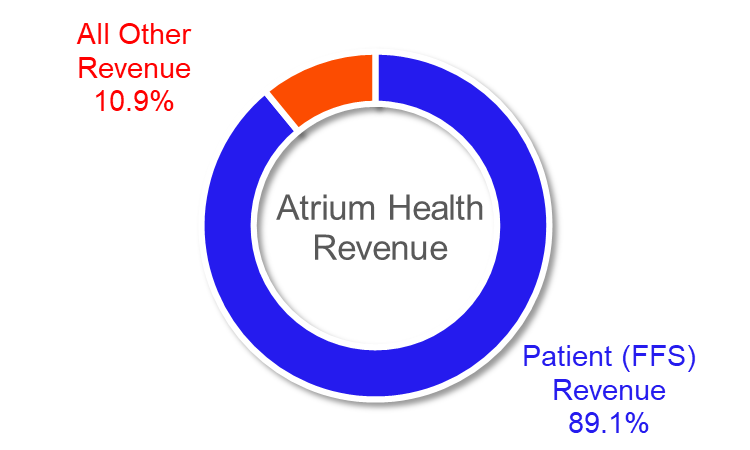

Atrium’s story is somewhat cleaner than Advocate Aurora’s because they are more clearly a FFS shop. In 2020, the system reported $6.4B in total revenue, $5.7B of which was dominated by net patient service revenue (read: FFS).

For those who reviewed Figure 1 thoroughly, you’re probably wondering about Atrium’s Medicare Advantage H-number. Atrium Health launched a Medicare Advantage PPO plan in collaboration with Care N’ Care Inusrance Company in January of 2019 (branded as Teal Premier).

The plan had 183 members in January of 19 and grew to 359 by December of 2020 before being discontinued (the plan is no longer reported by CMS starting in January of 2021). Importantly, Atrium is definitively further behind in the VBC game, but it is Atrium’s CEO that will ultimately assume the helm of the conglomerate.

Daran’s Verdict: Fee-for-Service dominates Atrium’s current operating model.

SCL.

Sisters of Charity of Leavenworth Health System (SCL) is the smallest of the field with 2020 revenue of $2.8B – almost exclusively FFS.

They did partner with Blue Cross and Blue Shield of Kansas to form an ACO in 2016, as the St. Francis Accountable Care Network (St. Francis Health was an SCL subsidiary before being acquired by Ardent Health Services in a joint venture with the University of Kansas Health system in 2017). The ACO no longer exists.

Daran’s Verdict: Fee-for-Service dominates SCL’s current operating model (which is what likely made it a great acquisition target for Intermountain).

Intermountain.

Spoiler Alert:

Of the four health systems analyzed, Intermountain is clearly the furthest along in the value-based care journey, with risk-based revenue sitting at just under half of total revenues. Since we led off with ACO’s in the previous three examples, it’s only fair to start with Intermountain’s ACO.

Source: Intermountain Investor Presentations

Castell Accountable Care Organization garnered $11.5M in 2020 savings on 52k Medicare beneficiaries in its two-sided model. In fairness, Intermountain’s 2020 savings per beneficiary is less than half the Advocate Aurora ACO average ($221/beneficiary vs $596/beneficiary in Figure 3). That’s about the only blemish (if you want to call savings a blemish) on Intermountain’s VBC track record.

Figure 3. 2020 MSSP ACO Performance

The system’s provider-sponsored insurance company SelectHealth serves more than 900k members and has demonstrated profitability (which isn’t easy for a provider-sponsored plan). In 2020, a year that insurers admittedly fared very well due to pandemic-driven care deferral, SelectHealth posted an astonishing 11% margin (a feat that no doubt helped the health system weather the volume drought that crippled the bottom lines of many FFS-dominant health systems).

Source: Intermountain 2022 not-for-profit presentation

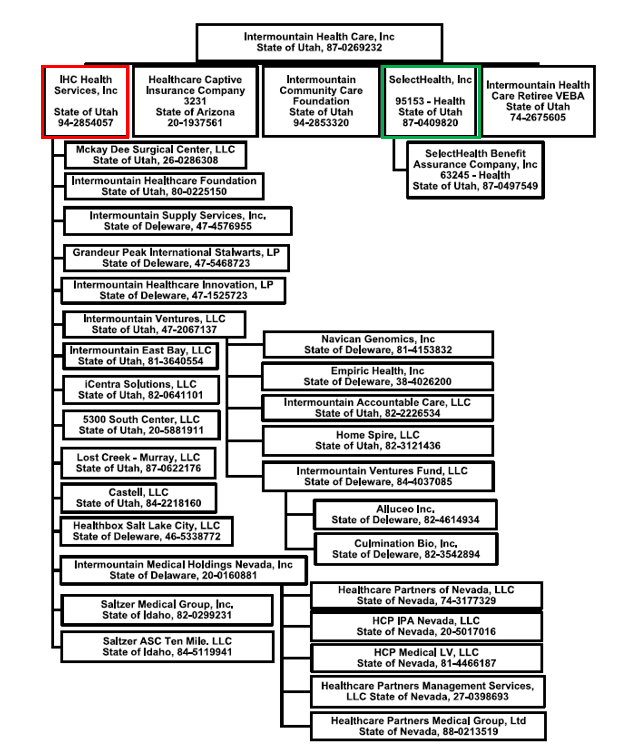

In 2021, this figure returned to earth at a still-healthy 4.9% net margin (payers typically have margins around 4.3%). Moreover, Intermountain built and spun out value-based care services company Castell in 2019 (although it still falls under the IHC Health Services subsidiary as shown in Figure 5).

Castell has been a key driver in Intermountain’s “Reimagining Primary Care” model around population health and value-based payment success, and has decreased MA admissions by 60%, commercial admissions by 25%, and reduced PMPM costs by 20%.

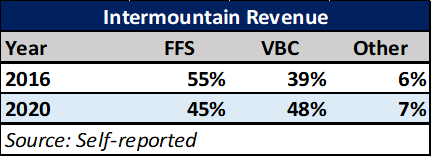

As you might expect, Castell manages Intermountain’s ACO and has been instrumental in implementing Intermountain’s hospital-at-home program. Intermountain’s collective value-based initiatives have been the drivers behind growing the company’s value-based revenue from a self-reported 39% of total revenue in 2016 to 48% in 2020 (Figure 4), figures that are consistent with the consolidated financial reporting captured in Figure 2.

Finally, Intermountain reports that prior to the merger with SCL, more patient-derived revenue came from value-based arrangements than from volume-based FFS.

Figure4: Intermountain Revenue Reporting

Daran’s Verdict: Value-Based Care dominates Intermountain’s current operating model.

Antitrust Considerations

With the new-age health system merger focused on vertical alignment in markets, hospitals have new antitrust guidance to watch out for – but right now, this type of antitrust review is more art than science.

The Federal Trade Commission (FTC) announced that it is reviewing its vertical merger guidelines last year. The FTC and Justice Department jointly published a revision in 2020, marking the first update since 1984. However, the reevaluation likely indicates that the federal watchdogs are about to take a harder stance on vertical integration.

It is worth noting that the DOJ is still rolling with the 2020 guidelines, so any FTC changes may cause incongruity. Why all the fuss? Well, the market impact of vertical integrations are notoriously hard to measure.

A far larger body of research exists for horizontal mergers (especially when they exist within the same geography). The Herfindahl-Hirschman Index (HHI) is a measure of market concentration, and a recent National Bureau of Economic Research study compared seven years of claims data to hospital mortality rates while noting each hospital’s HHI score and discovered that receiving care from higher-priced hospitals led to better health outcomes when exclusively in a relatively unconcentrated market (whereas there was no association between high prices and mortality at hospitals in concentrated markets).

However, the HHI doesn’t do as well when horizontal mergers occur in non-overlapping geographies, as there is no inherent change in each individual market’s concentration. Experts have noted, though, that the increased scale of such mergers may change the dynamics of negotiations with payers .

While private equity deals captured many headlines in 2021, health plans quietly dominated the physician practice acquisition space. United’s Optum acquired 10k practices last year (as well as finalizing the acquisition of Atrius and announcing the acquisition of payvider Kelsey-Seybold) and is now the largest physician employer in the U.S. (with 600k docs on the books). Humana has 206 primary care clinics, making it the largest operator in the PCP space (and just announced a $1.2B JV with WCAS to expand these).

Last year, CVS Health (owner of $82.1B insurer Aetna) added 10k pharmacists and PCPs to its roster. On the health system side, roughly 60% of health systems planned to enter the MA market in 2022. While integrating across the care continuum has the potential to improve outcomes and lower costs, the jury is still out as to whether or not value-based vertical integration will live up to the hype.

Conclusion

Value-based M&A is proliferating in new and interesting ways. There’s a significant economic case to be made for vertical integration as it enables the care delivery organization to own the whole patient and represents an essential feature of managing the total cost of care for a population. As a result, we should expect to see a lot more activity in this space by both payers and health systems.

We can readily conclude that Intermountain is conclusively a value-based care health system and that the other three are rooted in FFS land. The risk model proved to be extremely beneficial in 2020 as pandemic-related care deferral exposed the financial vulnerability of volume dependency (reference the operating margins in Figure 2) and the reliance on productivity and utilization to drive margins.

Just imagine what will happen when models like Intermountain begin to dominate nationally. Acute care volume will diminish again, except this time it will be due to healthier populations rather than a pandemic. This will have a deleterious effect on the health systems that have not moved to value and make them ripe acquisition targets for those that have.

As such, we predict that the Intermountain-SLC merger will lower prices and represents the cornerstone example of a new-age health system merger. On the other hand, history suggests that the Advocate Aurora-Atrium merger is likely to raise prices without requisite improvements in outcomes. Intermountain’s outlook stems from Intermountain’s desire to implement its value-based care platform into the SCL system. Advocate Aurora-Atrium’s outlook hinges on executive leadership and minimal material value-based success to date.

Could we be wrong? Absolutely. To that end, we do hope that Advocate Aurora is able to glean the lessons learned from its ACO and scale them across the burgeoning AAA conglomerate to improve outcomes and lower healthcare spending. Time will be the judge.

Want to get these in your inbox to never miss an edition? Subscribe to Hospitalogy today