Aledade made an interesting strategic move this week, and I wanted to jump into their reasoning behind becoming a public benefit corporation (PBC), what a PBC is, and how PBCs are a great fit for healthcare.

Also – you might get tired of the PBC acronym by the end of this.

Join 16,500+ executives and investors from leading healthcare organizations including HCA, Optum, and Tenet, nonprofit health systems including Providence, Ascension, and Atrium, as well as leading digital health firms like Tia, Carbon Health, and Aledade by subscribing here!

Public Benefit Corporations in Healthcare: Key Takeaways

Public Benefit Corporations (PBCs) are a hybrid corporate structure that sit between for-profit and nonprofit entities. Aledade and Mark Cuban’s Cost Plus Drugs are two marquee examples of PBCs in healthcare.

While the main goal of for-profit firms is to maximize shareholder value, PBCs impose another requirement of having some sort of ‘North Star’ purpose-driven mission outside of shareholder maximization.

PBCs are also more flexible than nonprofits in healthcare, which inhibit investment activity and introduce legal concerns when mixing for-profit and nonprofit.

The PBC matchup between shareholders and also public / social interests aligns well within US healthcare, which is currently a grotesque Frankenstein of capitalist and socialist aspects.

What’s a Public Benefit Corporation?

As mentioned, most companies fit into two primary corporate structures – for-profit and nonprofit. For you lawyers out there I’m sure there are nuances involved, but at a high level that’s what we’re dealing with. Here’s where things get interesting: a Public Benefit Corporation sits right in between the two and holds a few key differences:

- Rather than reinvesting all profits back into the organization in the case of a nonprofit, PBCs can distribute profits to shareholders (dividends).

- Instead of its main incentive as maximizing shareholder value as in for-profits, PBCs balance both shareholders and its stated public benefit mission.

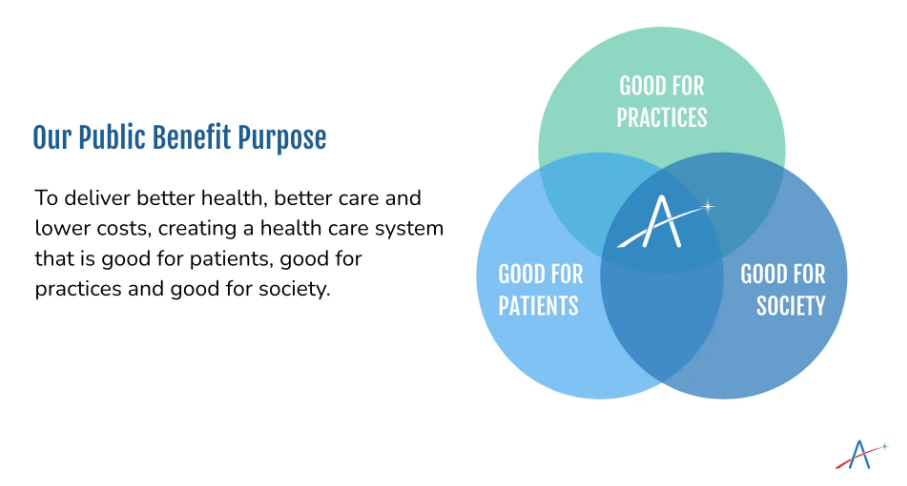

In Aledade’s case, its stated public benefit purpose is “To deliver better health, better care, and lower costs, creating a health care system that is good for patients, good for practices, and good for society.”

Why Public Benefit Corporations fit Healthcare so Well

There’s a central conflict in in U.S. healthcare sits between maximizing shareholder value and maximizing societal good for patients. Folks sit on both sides of the aisle, but I’d argue that most are somewhere in the middle. It’s been discussed a fair bit that the incentives in healthcare don’t align. Nikhil Krishnan put it in succinct terms in his post on the main problems with US healthcare:

“…the US isn’t sure if it wants the government to make decisions or free market competition to adapt to consumer interests. Currently, it’s the worst of both worlds. It’s regulated enough to make it difficult for new and small businesses to compete, while also free market enough to gouge the vulnerable.”

Here’s where the PBC comes into play. It sits in the middle. The PBC structure fits a compelling role between for-profit and nonprofit shenanigans in healthcare, namely:

- Healthcare organizations deserve to make margin for delivering good care and should receive returns on investment, but

- Stakeholders in healthcare also should be held back by public interests, and governance structure should reflect that.

Examples of Public Benefit Corporations in Healthcare

The best examples of public benefit corporations in healthcare today are Mark Cuban’s Cost Plus Drugs (MCCPD) and now…Aledade.

Cost Plus Drugs started off as a nonprofit. But Alex Oshmyansky, MCCPD’s brainchild, couldn’t raise any money.

In fact, Mark Cuban wasn’t interested in investing in Oshmyansky’s vision for Mark Cuban Cost Plus Drugs (MCCPD) until the model switched from a 501(c)(3) nonprofit org into a public benefit corporation. The initial vision of MCCPD wouldn’t exist at all without a PBC structure. From the D Magazine feature, the difficulties in starting without any sort of investment or equity incentives is impossible:

“[Oshmyansky] began in 2015 (the same year he completed his fellowship) by founding a nonprofit pharmacy company that was going to make drugs and sell them at cost. He formed a 501(c)(3) and set out to raise funds.

Join the thousands of healthcare professionals who read Hospitalogy

Subscribe to get expert analysis on healthcare M&A, strategy, finance, and markets.

No spam. Unsubscribe any time.

But this first endeavor crashed and burned. Oshmyansky didn’t raise a dollar more than he had invested. “It failed spectacularly,” he says.

But he didn’t give up. He found his way to Y Combinator, the Silicon Valley technology accelerator that has launched Dropbox, Airbnb, Reddit, Twitch, and others. The mentors there gave him some invaluable advice. They told him that the nonprofit model wouldn’t be able to raise the needed funds. But they liked his idea and suggested he launch as a public benefit corporation instead. Similar to a nonprofit, a public benefit corporation has the fundraising advantage of allowing the company to offer shareholders dividends. After reworking the business plan, Oshmyansky founded Osh Affordable Pharmaceuticals in 2018, and soon raised $1 million. It was a drop in the bucket when it comes to the pharmaceutical world, but it gave him confidence that he was onto something.” – my emphasis added

On the other side, Aledade started off as a venture-backed tech enabled enablement company to pursue physician practice independence. As late as June 2022, it raised $123 million in a Series E at a reported $3.1 billion valuation. Aledade was a scaled venture. Shifting to a public benefit corp wasn’t a decision that Farzad Mostashari and its execs made lightly.

But they realized that healthcare needs more.

From Farzad’s post: “Our business model compels us to maintain alignment with the interests of all these stakeholders – but more importantly, it requires them to BELIEVE that we will operate with their best interests in mind and at heart, over the long run. It calls for a fundamental shift in workflows, but also to share data and work together with traditional adversaries. Trust is at the very foundation of this model.”

Intrinsic to the structure of Public Benefit Corporations is one thing missing from the healthcare stakeholder alignment equation: trust.

Positive externalities of Public Benefit Corporations in Healthcare

As consumerism persists (albeit, perhaps to a limited degree) and bad actors get called out, the healthcare organizations building trust with all stakeholders – physicians, investors, patients, lawmakers, and insurers – will ultimately win. Here are a few reasons why PBCs could enable that future for organizations:

PBCs are high signal to consumers. in the case of Mark Cuban Cost Plus Drugs, the company is constantly finding ways to lower costs for consumers, and the cost-plus pricing model is radically transparent in stark contrast to the pharmaceutical industry and opaque pharmacy benefit management complex today. The thinking is that by doing so, MCCPD builds trust with consumers, which works as positive reinforcement for the brand and fantastic word-of-mouth marketing. These externalities – while not present on the balance sheet – lead to lower customer acquisition costs for MCCPD and higher demand for its services.

PBCs are high signal to other stakeholders. In the case of Aledade, the firm wants to attract primary care physicians and other partners to its platform in order to enable the shift to risk-based arrangements. Physicians talk. I would wager that an organization with a stated mission that aligns with shared goals would have an easier time attracting physicians to Aledade’s platform.

PBCs are high signal to employees and investors. Forming a PBC puts your foot in the ground. It says “we don’t want you unless you align with our stated purpose, because that’s a fundamental part of who we are as an organization.” In the same way it would attract physicians to the model, the firm will also attract like-minded investors and employees who share the goals of the org.

Potential Shortcomings of Public Benefit Corporations in Healthcare

Now, obviously I’m looking at PBCs through rose-colored glasses. In true Hospitalogy fashion, there are some definite, possible limitations to public benefit corporations in healthcare. Some thoughts:

PBCs may limit profits. By making decisions based on interests outside of financial ones, organizations may put themselves at a margin disadvantage as compared to pure for-profit players in the space. In healthcare, financial incentives are not fully aligned with patient care. As a result, what might be good for the patient or community isn’t aligned with maximizing profits (e.g., setting up shop in a low-income area rife with Medicaid). Consequently, PBCs may lose out on investment dollars allocated to more profitable services (if they exist).

PBCs may be unnecessary. If you have good corporate governance and leadership anyway and/or physician or clinician led experience in the C-suite, then do you really need to hamstring yourself by putting additional annual requirements and disclosures on the firm?

Is there true oversight and accountability for PBCs? What oversight is there? Can you just say you’re a PBC, put out an annual report on your mission statement, and will anyone actually check to see if you’ve changed your governance structure or created tangible improvement toward your stated objectives in healthcare? Are there any penalties for not doing so or is it all marketing fluff?

Would it actually solve problems in healthcare? E.g., would a PBC actually make a decision detrimental to its bottom line if it fits its stated benefit purpose?

Parting thoughts on Public Benefit Corporations in Healthcare

So…since pretty much every company is incorporated in Delaware, and Delaware has an easy fast track option to becoming a public benefit corporation…why don’t we just go ahead and switch everyone over?

Kidding, aha..unless?

If you have any thoughts on public benefit corporations in healthcare, or any answers to the above questions, I’d love to hear them. As always, I’m sure there is plenty of nuance I missed, but I’m here to drive the conversation forward – not backward. I’ve also linked a few resources I found helpful in reading about PBCs in healthcare.

Here’s hoping that others continue to follow in the footsteps of forward-thinking organizations like Aledade and Mark Cuban Cost Plus Drugs.

Resources:

- Why Aledade Became a Public Benefit Corporation (Aledade)

- Meet the Genius Who Convinced Mark Cuban to Sell Drugs (D Magazine)

- Public Benefit Corporations: A Third Option For Health Care Delivery? (Health Affairs)

- Converting to a Delaware Public Benefit Corporation: Lessons from Experience (Harvard Law)

- What’s the Difference between a Public Benefit Corporation and a B Corp Certification? (Hutch Law)

- All of the main problems with US healthcare (Out of Pocket)

That’s it for this week! Join 16,500+ executives and investors from leading healthcare organizations including HCA, Optum, and Tenet, nonprofit health systems including Providence, Ascension, and Atrium, as well as leading digital health firms like Tia, Carbon Health, and Aledade by subscribing here!