Intro

Happy Thursday, Hospitalogists!

The paternity leave guest posts continue with a fantastic write-up from fellow newsletter writer and Hospitalogy Board Room community member Ann Somers Hogg. Ann Somers is a Director of Health Care at the Clay Christensen Institute.

For the latest health care insights and analyses from the Christensen Institute, you can receive Ann Somers’ monthly newsletter and access the Institute’s work here. Go ahead and show her some support!

Finally, big shout out to Blakemore Consulting for sponsoring today’s send. I’m excited to partner with them, especially considering the shared namesake!!

SPONSORED BY BLAKEMORE CONSULTING

Network adequacy is a key factor affecting members access to care.

That’s why Blakemore Consulting serves payors of all sizes, in all lines of business, across multiple states, with high-quality turnkey network development services.

With over 150 years of collective experience, Blakemore Consulting offers an unparalleled focus on network development and adequacy, offering services like:

- Provider network builds

- Network analysis and strategy

- Provider contracting and recruiting

- Adequacy reporting and modeling

If you’re looking for comprehensive network development and adequacy service tailored to your specific needs, definitely chat with the folks at Blakemore Consulting.

Health care’s female workforce: The platform isn’t just burning; we have a raging fire.

Stress. Depression. Anxiety. Burnout. You’ve heard about the mental health problems facing our health care workforce. But what I share here is a new approach for how to address the stressors facing providers, specifically those plaguing nurses. Below, I provide a clear framework and tactics you can use to engage your workforce, improve employee health, and enhance your bottom line. Trust me, you want to read until the end. The next email can wait.

Female workforce: By the numbers

According to the Bureau of Labor Statistics, women make up 77.6% of the health care workforce, 86% of nurses are women, and many of them are parents. Last year, Health Affairs highlighted how the number of RNs had dropped by over 100,000 in 2021, the greatest drop observed in the last 40 years.

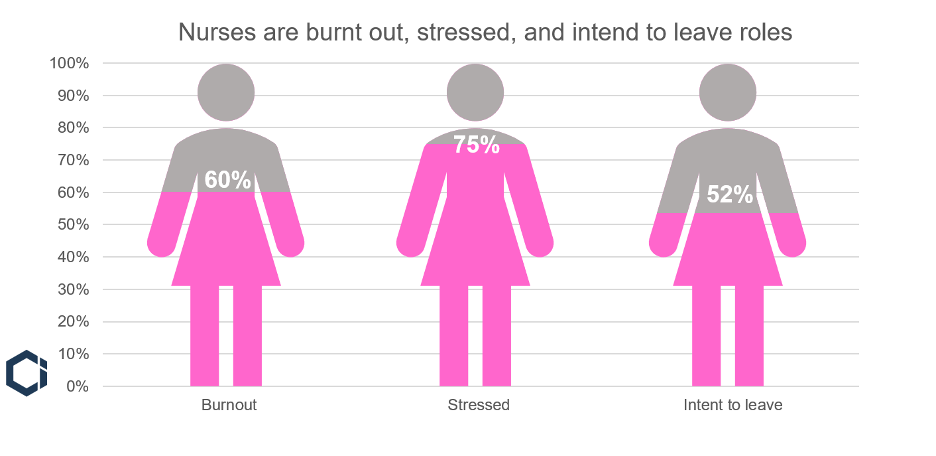

Additionally, the American Nurses Foundation’s 2022 study highlighted staggering statistics on the state of nursing in the US:

- 60% are burned out.

- 75% are stressed, frustrated, and exhausted.

- For nurses under 35, 66% are anxious and 43% depressed.

Unsurprisingly, the same survey found that 52% of nurses intend to leave their positions. Primary reasons for this include insufficient staffing and “work negatively affecting health and well-being.”

Figure 1. Nursing’s mental health crisis

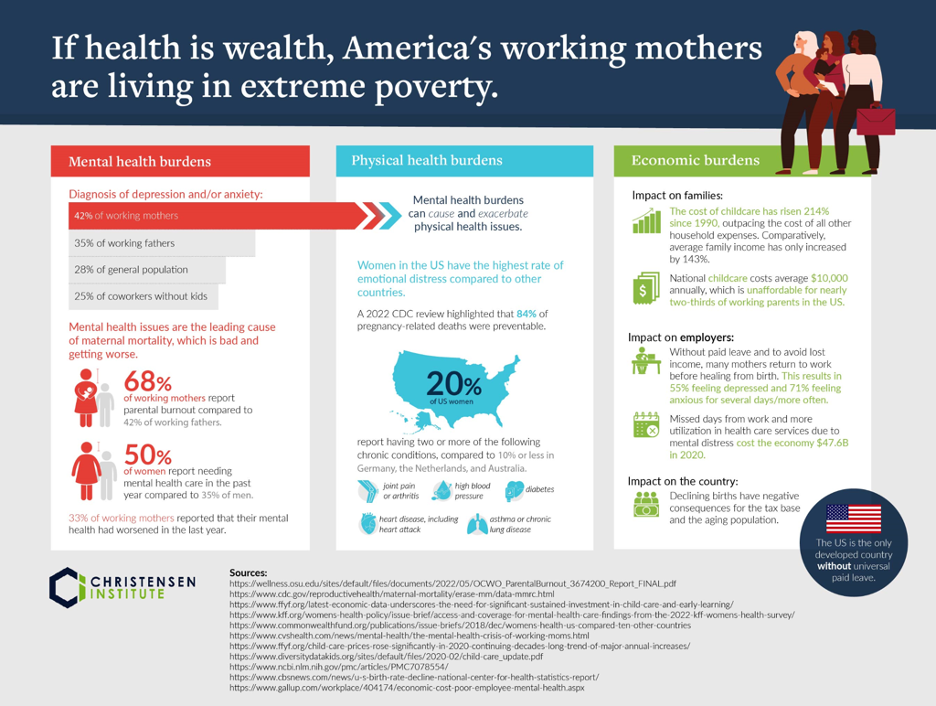

Similar issues burden the broader female population, especially working mothers. While health outcomes and declining life expectancy are plaguing the US population broadly, the infographic below highlights how mental, physical, and economic burdens are disproportionately carried by the working mom.

Join the thousands of healthcare professionals who read Hospitalogy

Subscribe to get expert analysis on healthcare M&A, strategy, finance, and markets.

No spam. Unsubscribe any time.

Working mothers are plagued by depression, anxiety, and burnout at higher rates than both working fathers and coworkers without children. Adding insult to injury, mental health issues are the leading cause of maternal mortality, which the CDC recently identified as preventable in 84% of cases. Health issues are compounded by economic distress, such as the cost of childcare, which has risen 214% since 1990, while average family income has only risen 143%.

A 2022 survey by the Bipartisan Policy Center (BPC) found that moms working in health care report that flexible work, paid leave, and affordable quality childcare would benefit multiple aspects of their lives at higher rates than moms working in other sectors.

Working women are stressed. It’s worse for mothers, and it’s especially bad for young nurses who are early in their motherhood. This does not bode well for the future of the caregiving workforce. However, all is not lost. Health care executives have tools at their disposal to improve the situation.

Tools of Cooperation: A brief primer

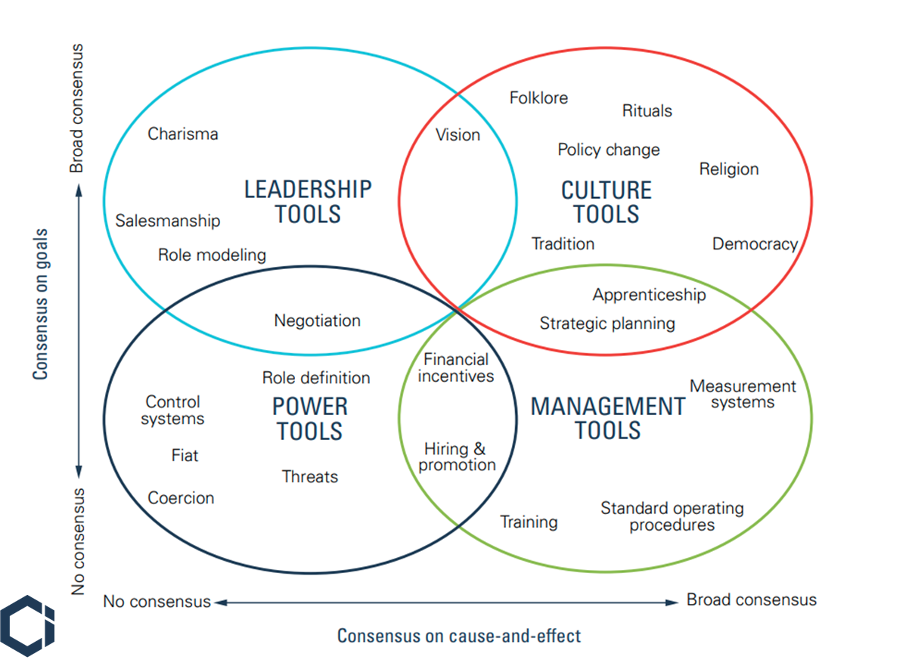

How can leaders convince individuals to work together to solve the problem at hand? There are a variety of tools, ranging from motivational, visionary speeches to command-and-control orders that an individual can use to elicit cooperative behavior. Late Harvard Business School Professor Clayton M. Christensen termed these the Tools of Cooperation.

The first important thing to know is that most of these tools don’t work most of the time.

As a result, leaders often fail when trying to manage change, since the tools they use waste credibility, energy, and resources. Therefore, the most important upfront action is to assess one’s circumstance in terms of stakeholder agreement on what the goals of the organization should be and how it can achieve them.

The graphic below depicts these two variables. First, the vertical axis measures the extent to which the people involved agree on the goals. In other words, what do they want? This incorporates the results they seek from being part of the community, to what their values and priorities are, to which trade-offs they are willing to make to achieve those results. The extent of agreement can range from none (at the bottom) to complete agreement (at the top).

The second dimension is plotted on the horizontal axis. It measures the extent to which the people involved agree on cause and effect—which actions will lead to the desired result. In other words, how will we achieve our goals? On the right-hand side, strong agreement on cause and effect implies a shared view of the processes that should be used to get any particular outcome, whereas little agreement on cause and effect places an organization on the left-hand side of the diagram.

Figure 2. The Tools of Cooperation

When it comes to poor and worsening maternal health broadly, especially for working moms, our society is—and has been—in the lower left-hand quadrant. That means we don’t hold shared goals for maternal health, nor do we agree on what to do to improve it.

Looking specifically at the health care industry, we are in a slightly different circumstance: the Leadership Tools quadrant. This is because industry stakeholders have broad consensus around a goal to have enough caregivers to sustain care provision both today and into the future.

But we don’t yet have consensus on cause-and-effect; that is, how we can achieve that goal.

This is where we need a forward-thinking health care entity to take the lead and role model a way forward for the industry. By prioritizing women’s health—and therefore, that of the nursing population—and instituting company policies that promote women’s health, not detract from it (i.e., working fewer hours, flexible work, affordable childcare, paid leave, etc.), leading organizations can demonstrate how their approaches reduce workers’ stress and burnout, and therefore, keep more women, working mothers, and nurses in the workforce.

The Path Forward

In my recent in-depth report on the topic of working mothers’ health outcomes, If health is wealth, America’s working mothers are living in extreme poverty: A framework for proper diagnosis and effective treatment, I provide detail on why the various national policy levers we have attempted to use to improve conditions for working mothers and parents more broadly have failed.

With limited space here, I’ll focus on what health care executives can do to right the ship and not only achieve the goal of sustaining care provision, but do it while achieving other key objectives of improving women’s health, enhancing their bottom lines, and boosting employee engagement.

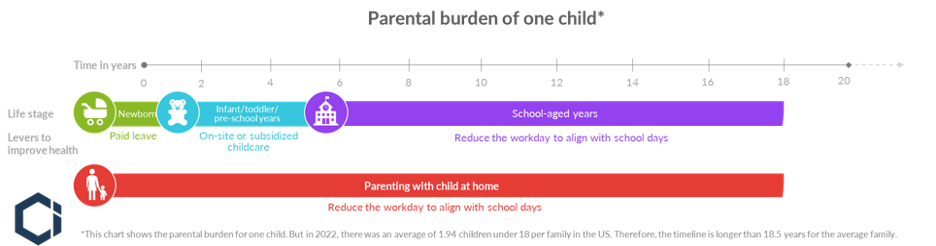

Looking at the typical timeline of parenting in the US (see chart below), the most effective lever to reduce maternal stress over the longest time period would be to reduce the misalignment between work and school calendars. In essence, this would involve reducing the average workweek from 40 hours down to about 30 hours, or for those working 12-hour nursing shifts, from 36 hours down to 30.

Working parents must juggle school schedules with work schedules, often dealing with gaps in overlap, inconsistency, and long summer breaks for at least 14 years after preschool.

Both six-hour work shift and four-day workweek studies show working fewer hours improves both health and productivity. In the latest four-day workweek study out of the UK, which reported results at the start of 2023, 71% of employees reported reduced burnout, 39% reduced stress, and 40% fewer sleep issues. Notably, fatigue-related burnout costs companies around $2,000/employee/year.

To address the nursing crisis, leading organizations could test a 6-hour shift approach. This approach proved effective at improving productivity, enhancing quality of care, reducing stress, and reducing sick days in a study of Swedish nurses. This might seem unfathomable when there is already a shortage of workers. However, with shorter shifts, nursing staff would have more of the flexibility they desire, as well as fewer hours to cover childcare—a notable stressor uncovered in the BPC study. Together, reducing these major stressors has the potential to keep more nurses in the workforce, and potentially attract others to, or back to, the field.

Conclusion

As a result of leveraging their power to create change by leveraging Leadership Tools (e.g., vision and role modeling), those willing to test the waters of alternative work arrangements can enhance the female workforce’s health and reap financial benefits.

A shorter workweek, or a shorter shift, is one of many recommendations that could have a positive impact on working mothers’ and the nursing population’s health. Additionally, it can boost our national prosperity. Did you know conflicting school and work schedules cost the US economy $55 billion in lost productivity each year?

Notably, fewer hours won’t be a fit for all employers in the near-term. What’s critical is that leaders agree that learning what works best for their employee population, and establishing broad consensus on a solution, are worthwhile investments. We don’t just have a burning platform for change, we have a raging fire and desperately need a course correction to sustain our health care workforce.

So, as a health care leader, what can you do? To start, set your vision, and demonstrate how consensus around the goals of sustaining the caregiving workforce and improving women’s health can not only benefit your organization, but can move us forward as an industry. The future of health care, and the women that power it, are counting on you.

If you enjoyed this, consider subscribing to Hospitalogy, my newsletter breaking down the finance, strategy, innovation, and M&A of healthcare. Join 23,000+ healthcare executives and professionals from leading organizations who read Hospitalogy! (Subscribe Here)